If Robert Eggers only gets one thing right in his version of Nosferatu, it’s that mankind will be saved by a woman. And the Messiah will be a very complicated girl.

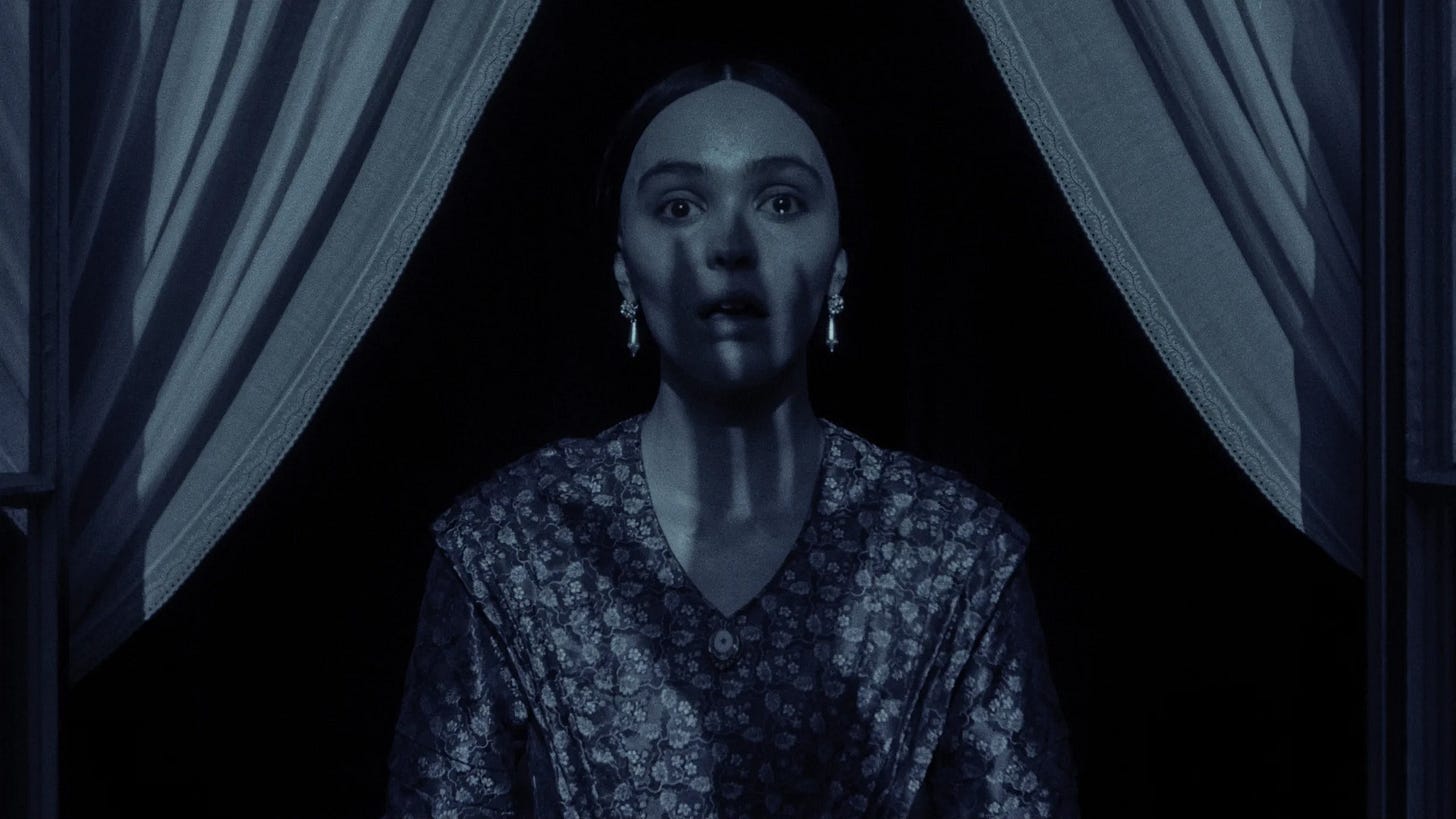

Eggers gets a lot of other things right, too, but in his vision for the vampire myth, dripping with more authentic cultural hoodoo than any previous version I can think of (including Stoker’s novel), its greatest strength — and weakness — is that Ellen Hütter (Lily-Rose Depp) is both airily defined and sharply portrayed. By the end of the film’s rather swift two-and-a-quarter hours, who Ellen is ends up being the ultimate mystery. Count Orlok (Bill Skarsgärd, adding to his monster collection) starts out as the thing in the shadows, the unknowable, the unmentionable (until Willem Defoe’s alchemist professor gives him a name), but as the film goes on he becomes something of a pathetic figure, owned and doomed by his connection to Ellen. Orlok is, in the end, a simple creature. What his connection to Ellen is remains foggy. It is ancient and powerful and supernatural and perhaps, rather conveniently, also unknowable.

Eggers does seem more interested in the metaphor than the plot — and it makes for a powerful essay on the historic position of women’s mental health in privileged society (as well as all the other things he seems to be saying through Ellen’s story). And make no mistake, Eggers’ Nosferatu is Ellen’s story. This is a film about women, an attempt (people will disagree on whether it succeeds) at a feminist horror movie. It is complex, somewhat unsatisfying in its proclamations, but compelling, bold, dream-like, nightmare-like, shocking, fun, and some of the set-pieces demand the film gets repeat viewings, but the misty nature of its themes will no doubt divide opinion.

The bad things: some of the dialogue seems hard to deliver, particularly the excruciating exchanges between Nicholas Hoult’s Thomas and Aaron Taylor-Johnson’s Friedrich. Some of what they say to each other is so poised and lumpy you have to assume it’s a writerly affectation that has failed to hit the mark. It’s as if AI has written a 1970s BBC period drama. Equally, a scene where Emma Corin’s Anna tries to make small talk with Ellen during a leisurely morning stroll had me gasping with laughter.

Aaron Taylor-Johnson, an actor I like, is not good in this. Stories of a complicated casting process suggest he is, indeed, miscast. That is a shame. It makes you wonder if the Dracula story can ever be truly successful on screen. No version has ever been peopled without fault. There is a long list of shit vampires, from Jack Palance to George Hamilton, and the supporting players have included such carpentry as Roy Castle and Keanu Reeves. Herzog’s Nosferatu is a speck of gold, granted, but it’s difficult to watch Kinski in anything given his real life evil. The marvellous Shadow of the Vampire has the acting abomination that is Eddie Izzard.

Good things: reviewers and just viewers have opined long and hard about the successes of Nosferatu. I would only be echoing them here. But I would like to emphasise the accomplishment of Eggers in realigning the cultural phenomenon of the vampire with the folk stories from which that monster has emerged. I had been expecting (and looking forward to) an update to the iconic Max Schrek invention, similar to what Werner Herzog and Klaus Kinski did with that version in the late 1970s. But Eggers has sidestepped that vision, and by deepening the connection to the vampire origin he has deepened the literature of the movie. The vampire is no longer a handsome gentleman, and neither is he verminous scourge. He is a manifestation of an ancient evil, a corruption of nature, a harbinger, a banshee, the bringer of plague, but when he feeds he relinquishes himself to the need, he is vulnerable, lost, conquered. Gone is the sexy bit of neck (although Eggers’ camera has something of a fetich for throats in this film), the hypnotic gaze (although Orlok certainly has a supernatural magnetism about him), the cape and collar (not to take anything away from the Count’s lavish overcoat). So much of Eggers’ Orlok is an echo.

In the end, Orlok the monster is perhaps just a brute out of time, a medieval Wallachian warlord possessed by a demonic spirit. He cannot love, but what he has in place of that is what so many men have. He is cruel and selfish and single-minded, and he will destroy everything and anything to satiate is unspecified connection to Ellen. They have, it is stated, reconnected after something we are left to assume was a childhood trauma that gave birth to this manifestation of damaged mental health. Lily-Rose Depp, interestingly, is much better when free of the shackles of the dialogue she is expected to deliver. She understands Ellen better as a wreckage. Once she gets going, she delivers an astonishing, visceral performance. There is no doubt by the final curtain that the men, for all their energy and gurning and stamina, don’t have what it takes to kill the beast. But we know that Ellen does. As she shrinks violently from the people around her, she grows into something else — a mother to all men, caressing unto death the problem child so that the good can live on.

Spot on, methinks. Saw this on a big but murky screen and the only thing I really managed to enjoy was the sound design. Laughable dialogue. Was glad to see Defoe take the Hopkins approach to the whole silly affair and no amount of beautifully gloomy cinematography could stop me from being disappointed by the “echo” of it all.