Chasing my 3-year-old into a forbidden room (his grandparents’ bedroom, no less) something on the rickety bookcase in the corner caught my eye. A book I had not seen in a very long time, even though in the last few years I had written about it at length, and with a lump in my throat.

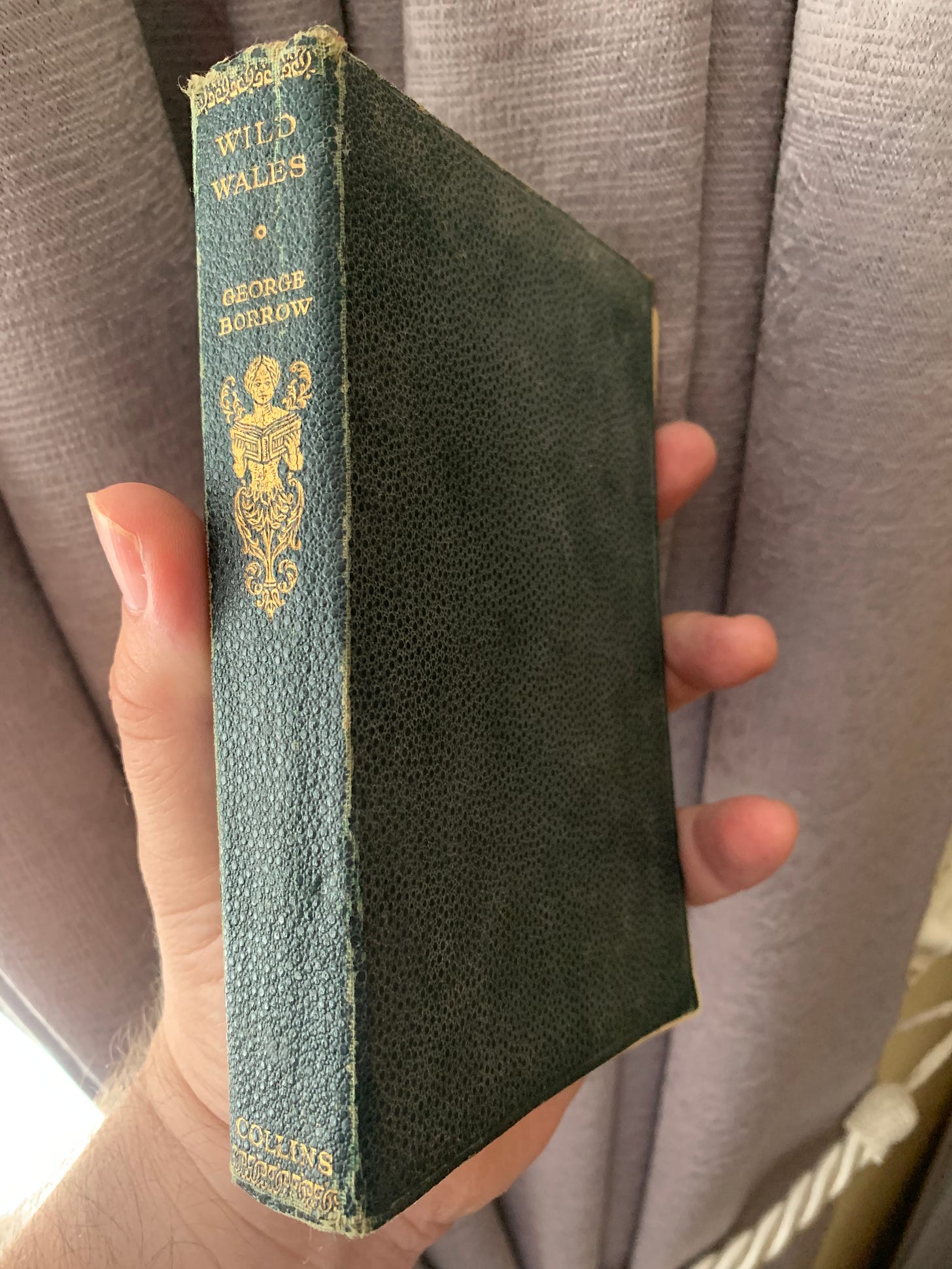

There it was, the copy of George Borrow’s Wild Wales that I had carried around with me in my youth, my grandfather’s copy, passed down.

I told the story of my relationship with this battered old edition in Abandon All Hope. Here’s the entry for its author.

In my childhood, I had an image in my head of George Borrow as a quiet, genteel, observer of the human spirit – perhaps something like a tweedy rambler who enjoyed a pint of ale and mild pipe at the end of a long day’s trek down the canal paths and walkways of nineteenth-century Wales. But Borrow wasn’t quite so bathed in the serenity of such a nostalgic, retiring, portrait.

In fact, Borrow was a fierce, masculinist, in-your-face iconoclast who built up a considerable readership with books about the Church in Spain, only to turn many of them off with his virulent dismissal of romantic attitudes in favour of championing the more manly pursuits of drinking and fighting. When I decided to follow his pub visits detailed in Wild Wales, I had no idea just what a man’s man Borrow was. Born in Norwich, Borrow was tutored by a friend of Robert Southey, and dazzled his elders with his linguistic skills. By the age of twenty-three he had already published a translation of Faustus from the German and a book of Danish romantic ballads. In 1835, working with a German publisher in St Petersburg, he published Targum, which included translations of works from over thirty different languages.

But by the 1850s, his success with his book The Bible in Spain, which was highly critical of Rome’s cultural influences, and his affiliation with gypsy communities he had discovered during his extensive travelling around Europe gained him a reputation as what Meic Stephens called the “high priest of the vulgar taste”. In reality, he was simply an anti-establishment figure of the type rarely found in that sphere, and all the bolder for it.

Perhaps it was this sincere connection to the oppressed that drew him to the Welsh. He had been fascinated by the language ever since one of his father’s grooms had spoken it to him when he was a young man and it formed part of the central circle of linguistic marvels for him. He translated several Welsh works into English, including one of Ellis Wynne’s Gweledigaetheu y Bartdd Cwsc (1703) into The Sleeping Bard in 1860. But it is for Wild Wales that he is best remembered, even though, due to his soiled reputation rendering him a cultural neanderthal, it did not sell well at the time of its release in 1862. The George Borrow Society sums up the tour best as thus:

On 27th July 1854 George Borrow began a tour of North Wales which would last until 16th November 1854. The Borrows lodged at Dee Cottage, Llangollen, and from there Borrow started local excursions, followed by a long walk via Corwen, Capel Curig to Bangor and Holyhead (and lots of other places). Then in September he headed south via Caernarvon, Beth Gelert and Festiniog and back to Llangollen. October saw the start of a long walk to Bala, Machynlleth, Devil’s Bridge, Strata Florida, Lampeter, Llandovery, Swansea, Neath, Merthyr Tydvil, Caerphilly and Newport, finally ending up at Chepstow on 16th November 1854.

The result is a magical travelogue, and one that lends itself so well to the matching of the contemporary with the old. BBC Wales have missed a trick (unless I have missed them not missing it) by not giving some charismatic celebrity a first edition of cracked leather, like Michael Portillo has done with his Bradshaw’s Handbook, and setting him or her off around the country with an intrepid camera crew.

Wild Wales has always been divisive and controversial. Jan Morris, a great admirer of it, still called it “variously irresistible and insufferable”, as its author could be. Others have taken exception to the frequent patronising tone and self-aggrandising moments of Wild Wales, and dismissed it as another example of an Englisher looking down his nose at the Welsh. And so Wild Wales is a complex offering, and as much about the larger-than-life man at the centre of the book as the country and language he fell in love with.

Gary Raymond is a novelist, author, playwright, critic, and broadcaster. In 2012, he co-founded Wales Arts Review, was its editor for ten years. His latest book, Abandon All Hope: A Personal Journey Through the History of Welsh Literature is out now with Calon Books.